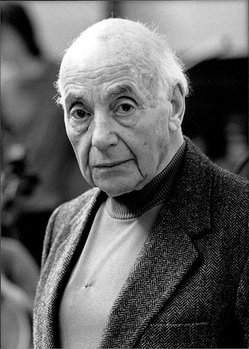

My "English" cousin Berthold--my mother's first cousin--passed away 20 years ago this week at the age of 93. He was a prize-winning composer and conductor of great early promise in Weimar Germany, but his success got him denounced as "degenerate" under Hitler's draconian Nuremberg laws (enacted in 1935) which prohibited Jews from engaging in most liberal professions and artistic undertakings. Goldschmidt, despite his many awards and strong ties to Germany's musical elite in the 1920s (he had been an assistant conductor at the Berlin Opera), was no match for Germany's newly legalized anti-semitism. Dismissed. Gave music lessons to survive. One day, a sympathetic SS officer, whose daughter was taking lessons from Goldschmidt, and who discussed Schumann and Schubert with him, whispered some stern advice: "Get out of Germany as soon as you can."

My "English" cousin Berthold--my mother's first cousin--passed away 20 years ago this week at the age of 93. He was a prize-winning composer and conductor of great early promise in Weimar Germany, but his success got him denounced as "degenerate" under Hitler's draconian Nuremberg laws (enacted in 1935) which prohibited Jews from engaging in most liberal professions and artistic undertakings. Goldschmidt, despite his many awards and strong ties to Germany's musical elite in the 1920s (he had been an assistant conductor at the Berlin Opera), was no match for Germany's newly legalized anti-semitism. Dismissed. Gave music lessons to survive. One day, a sympathetic SS officer, whose daughter was taking lessons from Goldschmidt, and who discussed Schumann and Schubert with him, whispered some stern advice: "Get out of Germany as soon as you can."

Wasting no time, Goldschmidt decamped, alone, for London, where he rented a coldwater bed-sit on Belsize Crescent; he would remain there for the next six decades. With a refugee's ability to adopt and adapt, Goldschmidt became more British than the British. Goldschmidt's wife, who was not Jewish, arrived from Berlin, heating was eventually installed, and Berthold found (menial) work as a rehearsal pianist and as a pit conductor for West End musicals. He provided dutiful commentary on his former rivals for the BBC. He gave music lessons, he conducted at Glyndebourne. Our family (the Americans) would visit him in London and take tea at Swiss Cottage, or meet in his beloved resort of Ascona, on the Lago Maggiore; he loved the mountain air but not the waterfront crowds, and would spend his holidays at a modest pensione, the Scacciapensieri, in the hills above the town.

In the late 1930s, Goldschmidt had led a remarkable BBC propaganda effort to showcase music by Jewish composers (Mendelssohn, Mahler) and performers (Kreisler, Schnabel). The broadcasts were beamed to Germany with the objective of undermining the Nazi government's claim that Jewish artists were "degenerate," The program didn't last all that long, and was dismantled after the war ended. His own music was rarely, if ever performed; it wasn't so much controversial as out of fashion. He actually won a blind competition for a Jubilee opera ("Beatrice Cenci") to be performed in honor of the Queen Mother's 50th year on the throne, only to find that English anti-semitism, though disguised by upper class manners, was no less virulent than the German variety; the opera was never staged. (Even Churchill, lest we forget, was a notorious if closeted anti-semite.) Too many melodies, too much "bel canto," was the excuse. Stung, Goldschmidt stopped composing entirely for the next 30 years.

A lesser man would have given in to despair. Berthold, however, never lost his energy; he would brave the elements daily for long walks on Hampstead Heath. He also began working on a years-long project with the musicologist Deryck Cooke to restore the "lost" 10th symphony by his idol, Gustav Mahler; he eventually conducted its premiere. Then, in the late 1970s, his wife died of leukemia, and Goldschmidt, almost 80, seemed to have reached the end. But quite unexpectedly the work of so-called "émigré" composers was featured in a concert series sponsored by the conductor Simon Rattle, beginning with a previously unheard Goldschmidt piece, Ciaccona Sinfonica. It would prove a turning point in England's musical and cultural awareness of Jewish composers: attention was suddenly paid to a whole category of persecuted artists whose work had been deemed degenerate by the Nazis. Goldschmidt acquired a major publisher, Boosey & Hawkes; his early compositions received performances in concert halls across Europe, and at the Proms in London. Yo Yo Ma performed his cello concerto in London; Decca set out to record his entire life's work. Miraculously, Goldschmidt began composing again at the age of 80.

Even "Beatrice Cenci" was eventually performed in 1988, at London's Queen Elizabeth Theater, to tumultuous success, None of Goldschmidt's old tormentors, however, were still around to see his triumph. ("I miss my enemies," he told the BBC. Also: "Bitterness is an acquired taste.") Even so, in 1996 a pair of German film makers produced an hourlong documentary about Goldschmidt; the signature line: "Man muss einfach nur überleben!" -- you just have to survive. The British musicologist Norman Lebrecht bemoaned England's small-mindedness in stifling Goldschmidt's creativity. "He had arrived with a massive competence and priceless experience," Lebrecht wrote, in a column in 2001 that concluded, woefully, "He could have taught this country the craft of music, if not the art, were it not for the insurmountable rocks of small-mindedness and little-englishness. ... The loss is as much ours as it was Berthold's."

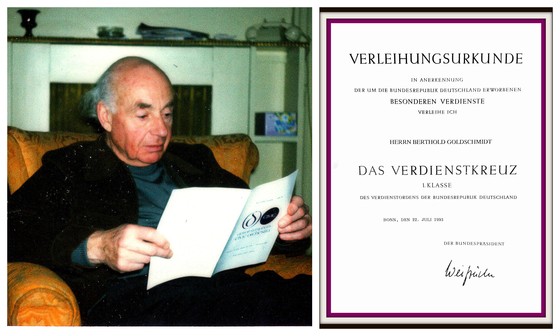

There's a happy ending of sorts to this story. In 1993, when Goldschmidt was 90 years old, the German government finally made amends and awarded him its Verdienstkreuz Erste Klasse, its National Order of Merit. His works (manuscripts, ephemera, CDs) are enshrined at the Akademie der Kunst in Berlin, and his musical legacy is preserved. His musical renown these days remains modest at best, however; contemporary orchestras (and classical radio stations) don't play his exquisitely wrought compositions. Unlike his contemporaries, Britten and Hindemith, Goldschmidt is still considered "old-fashioned." And yet. Amazon offers several dozen CDs of his music, easy to sample and easy to admire. A fine voice in a major key, diminished but not extinguished.

Goldschmidt photo above by Denzil McNeelance, Camera Press (Times) London, 1988. Below, from family archives.

Leave a comment